Josh Tonies with HereIn

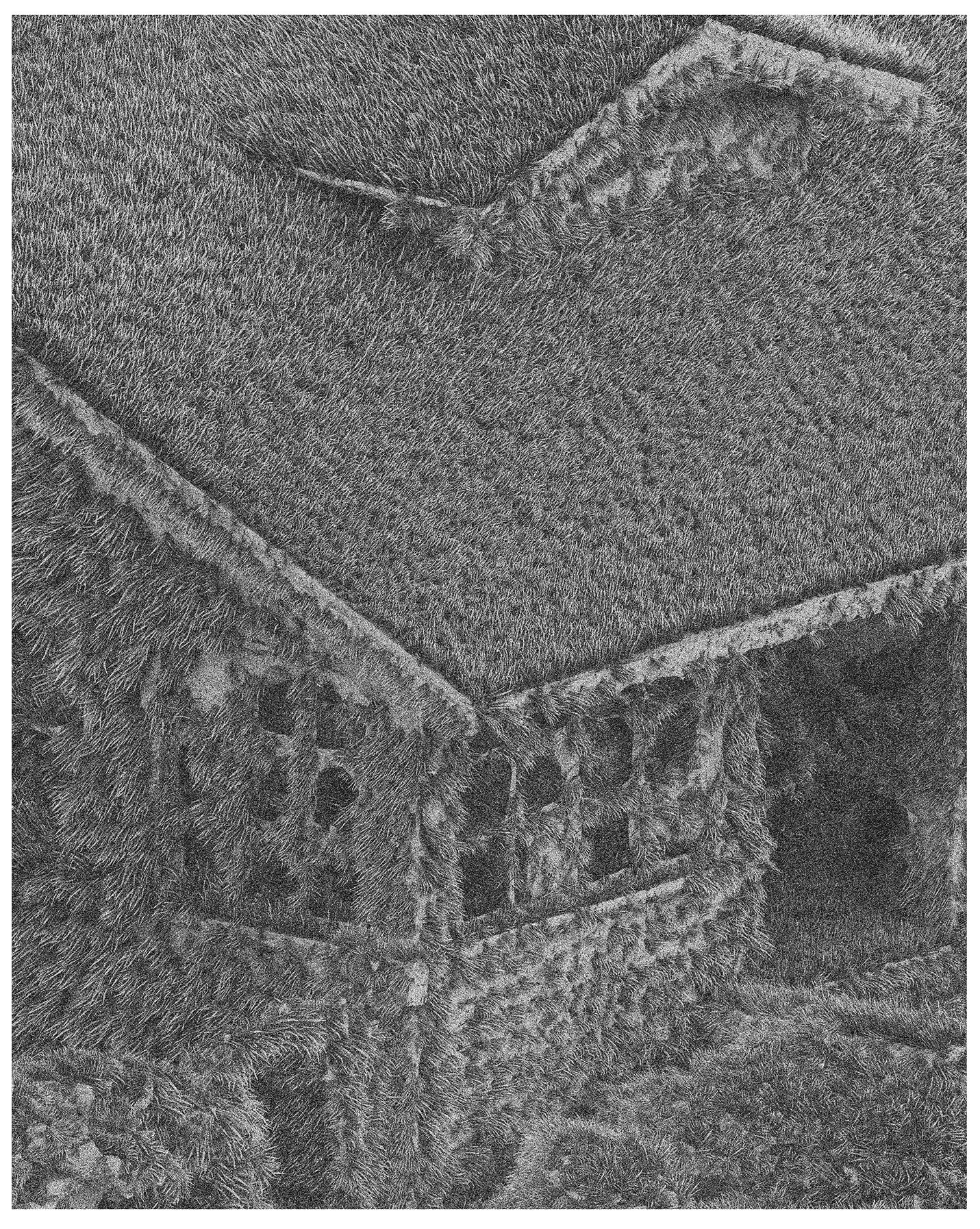

Bancroft veranda enclosed, 2023, mezzotint, 22 x 16 in.

[Image description: A corner view of a house covered in plant growth, all rendered in shades of gray.]

Artist Josh Tonies crafts nuanced studies of the natural environment, delving into ecological phenomena with works that are both scientifically-engaged and deeply poetic. He spoke with HereIn Editor Elizabeth Rooklidge about geologic time, queerness and adaptability, and the pandemic-induced anthropause.

HereIn: I’ll start with a question I really like to ask artists—what are the primary interests that drive your practice?

Josh Tonies: I guess one of my primary interests is finding ways to reflect my experience of the world in terms that allow people to reconsider their relationship with the natural world. That might seem open-ended, but one thing I see repeating in my work is an interest in geologic scales of time, where maybe the granularity of time seems almost invisible or seems as if there's no change. We can't see mountains move, but they're moving. Or the faces of rocks will erode over time, but we won't really witness it in our lifetime. But there's enough evidence that we know these forces are occurring. I think it's about framing the world or our experience in ways that this abstraction of time becomes tangible and we have access to it.

Kringla Heimsins (detail), 2013, digital interactive work with motion depth sensor

[Image description: An illustration of yaks and deer in a landscape, rendered in subtle tones of blue, pink, orange, and red.]

I grew up in northern Ohio. We lived in midtown Akron, which was, for Ohio, a dense urban environment. We were encouraged to know our neighbors—we were involved in their lives, and we played with kids in the neighborhood. When I turned 11, our family moved to this tiny town called Bath, Ohio. We lived on a plot of land that bordered the state park system, so it was a very alluring, beautiful forest and there was a ravine behind our house. Me and my brothers would play out there. I was kind of under the delusion that a lot of people had access to this and it was a common experience. But being in a space like that, where I got to spend a majority of my playtime in the environment, definitely informed my ideas about the wonder of the natural world.

La brizna de hierba viajera, 2020, 3D animation/video

[Video description: A sweeping view of a house covered in grass, standing in a grassy landscape. Wind rustles the delicate vegetation.]

HereIn: I see an interesting dichotomy in this; you’re talking about these enormous spans of geologic time and then details of your personal history, which are so intimate and are a lot about relationality and the body in space.

Tonies: Yeah, you're absolutely right. I guess I think about that work La brizna de hierba viajera (The traveling blade of grass). I lived in that house for 10 years. During that time, I completed my graduate studies, met my husband, started working in higher education, had a deadly tumor removed from my skull, and a whole host of other minutiae. The inspiration for the work came up at the outset of the Covid pandemic lockdown, so we were spending a lot of time there. I wanted to create this temporary image of our lives during this time, to document it, so I made a 3D scan of the house. And it started as a really paranoid work, something I didn’t think I’d show to anyone. It was made for myself.

It was early enough during the pandemic that I wasn't really sure how this was going to play out. I was a little cavalier when things were starting, before the lockdown happened. I didn't think that it was going to be this apocalyptic moment but I was thinking about the transmission of the virus through the air. And there was also this idea about the “anthropause,” that while we were in the state of sheltering or pausing, the natural world was continuing. There were dolphins in the canals in Venice.

One strategy I thought of was, like, what if—in a not-horrific way—what if humans didn’t exist? What would the world look like if things continued? So the idea of making the ruins of this house as a soft sculpture using these artificial, simulated materials came forward. And to speak to your question, I think I was able to work with a subject that was deeply personal to me by creating some level of estrangement or distance from it through representation. The image has this fantasy quality to it where the aesthetic of ruins almost takes a backseat to movement, the way that it's activated by wind. So I wanted to have this ecological reflection that stemmed from an embodied point of view. The house was, in a way, a representation of a body, the erosion and dissolution of it. Ruins queer our understanding of space by existing as neither fully part of the natural landscape nor entirely human-made structures. They disrupt a binary between natural and built environments. The physics simulation of wind in the animation brings attention to the materiality of air. The wind's interaction with the grass, and by extension the house, showcases the transformative power of air and its ability to alter and define the character of space.

Left: Bancroft exterior rear, 2023, mezzotint 22 x 16 in.; Right: Bancroft roofline, 2023, mezzotint 22 x 16 in.

[Image description: Two closeup views of a house covered in plant growth, all rendered in shades of gray.]

HereIn: When I watched the work, I found it to be deeply comforting. The ease I feel around issues of the world’s post-human existence might speak to my ingrained sense of fatalism, but you said something in an artist talk about the resilience of nature, which I think touches my emotional reaction to the imagery in a more hopeful way. Does that response resonate with you?

Tonies: Absolutely. The idea that there was a kind of joy or a sense of excitement in your emotional reaction to it, that it was uplifting—that is really important to me. I would love for the work to have the potential to be affirming and remind people that these systems are very directly affected by us. We see evidence of it constantly. They're not indifferent to us, but they'll continue when we no longer exist.

Aberrant Phytology, 2023, stop-motion animation

[Video description: A fern grows from a small shoot to a fully unfurled branch. At the end of the video, the fern becomes out of focus.]

HereIn: This all makes me think back to something you said in an artist talk, about the connections among time, change, and queerness—I believe you called queerness a continual “becoming.” Can you tell me a bit more about the relationship among these elements?

Tonies: Sure. If I can trace it to a specific work, it’s these weird time lapses of plastic succulents growing in domestic spaces. I don't know if it was clear to you how I made them, but they were a kind of reverse process where I took fake, dollar-store plants and cut or pruned them, then reversed the process. I loved how mutable the forms were and how easy they were to work with, but also their ability to represent a natural process while also doing something that was completely different. I was thinking that these do still convey this idea that the plants are growing, but it’s sort of an alternate process. And I guess I was connecting it to something that was a kind of queer framework.

It's fascinating for me how these artificial forms can so convincingly imitate the natural process of growth. I was initially concerned about representing them through scientific observation, so that they felt real, but the longer I worked with them, I realized what's really compelling about these works is their material.

They're crafted from Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and acrylic fibers, substances that are essentially ancient, fossilized life repurposed into modern forms. This project, in a way, revives these long-gone materials, giving them a new narrative in our contemporary world. For me it’s found tension as an exploration of our complex relationship with nature and history, viewed through the lens of modern materials and practices.

But for me these plants aren't just artificial imitations; they represent something deeper. They exist in a realm between mimicry and counterfeit, blurring the lines of what we perceive as real. This aspect of the project reflects the experiences within the queer community—the fluidity of identity, the adaptability in different contexts, and the concept of “passing” in various environments. These plants, constantly transforming and defying static definitions, resonate with the queer experience of navigating and reshaping spaces. In essence, they symbolize the ongoing journey of self-exploration and redefinition, a narrative central to both the queer community and the broader human experience. It merges natural imitation with a playful challenge to our perceptions of reality.

Arctic Immersion, 2019, hand-drawn animation

[Video description: A series of abstract, organic images in shades of black, gray, and white. The forms—in motion and still—are by turns ink-like and crystalline, shifting while the viewer watches. An audio track of underwater sounds accompanies the video.]

HereIn: A significant part of your practice is collaborative—you’ve worked with artists, scientists, engineers, and more people in a variety of fields. I’m particularly excited about your upcoming project with your fellow San Diego artist Joe Yorty. I wonder, what do you think collaboration brings to your practice?

Tonies: When you make something in your studio and then you release it out of its paranoid existence, you're relinquishing some control over its narrative. It's like, okay, what do y'all think? What are you seeing or feeling? And I think when you invite someone into a space like that, you’re incorporating some of the logic that this isn't completely mine anymore. But I'm here. So I love it because, in some instances, it forces you to be really generous and vulnerable, but it also creates a situation where you get to see into someone's thinking artistically in a way that you probably would never get to engage.

This conversation has been edited by HereIn and the artist for length and clarity.